Macron Is a Cursed Leader

When tangible success meets subjective prejudice.

In France, president bashing has a long tradition, from which even Emmanuel Macron has not been spared. This form of prejudice hasn't necessarily been evenly distributed among all French leaders, and besides the popularity rating, there aren't any reliable indicators when it comes to measuring the intensity of resentment towards a public figure. In comparison to previous mandates, I've rarely observed such a high level of hatred towards a French president, I could think of when Macron was slapped during a public event, or more recently, the incitement of a popular French singer to “hang” Macron – a statement she later regretted, claiming that her words were taken “out of context”. Other artists have also expressed similar attitudes, including the rock band Shaka Ponk or the US beatmaker Marc Rebillet. I won't mention the hateful comments I've seen online, because I'd assume that these occurrences are systematic for any political leader, although many of them were frighteningly threatening. Those who live in certain areas of Paris can attest to the fact that anti-Macron sentiment has become so pervasive that car insurance fraud has never been easier, since all you have to do now is park your car decorated with Macron posters in a protest avenue. And while most newspapers tend to focus on social issues rather than the big picture, The Economist recently published a surprisingly optimistic view of France: “Beneath France's revolts, hidden success”.

Recently France has even outperformed its big European peers. Since 2018 cumulative growth in GDP in France, albeit modest, has been twice that in Germany, and ahead of Britain, Italy and Spain.

Yet France on Mr Macron’s watch has managed to combine a more favourable attitude towards wealth creation with a welfare state that still does a better job than its big peers at correcting inequality. The French poverty rate is well below the average of its European neighbours, and little over half America’s. Nursery education, a proven means of improving life chances for lower-income groups, is now compulsory from the age of three. The French live six years longer on average than Americans, and far fewer are obese. Their jobless rate, at 6.9%, is at its lowest in 15 years. Despite Mr Macron’s reforms, the French state still takes more in taxes as a share of GDP than any OECD country bar Denmark—and devotes more to social spending.

Macron's rational irrational hate

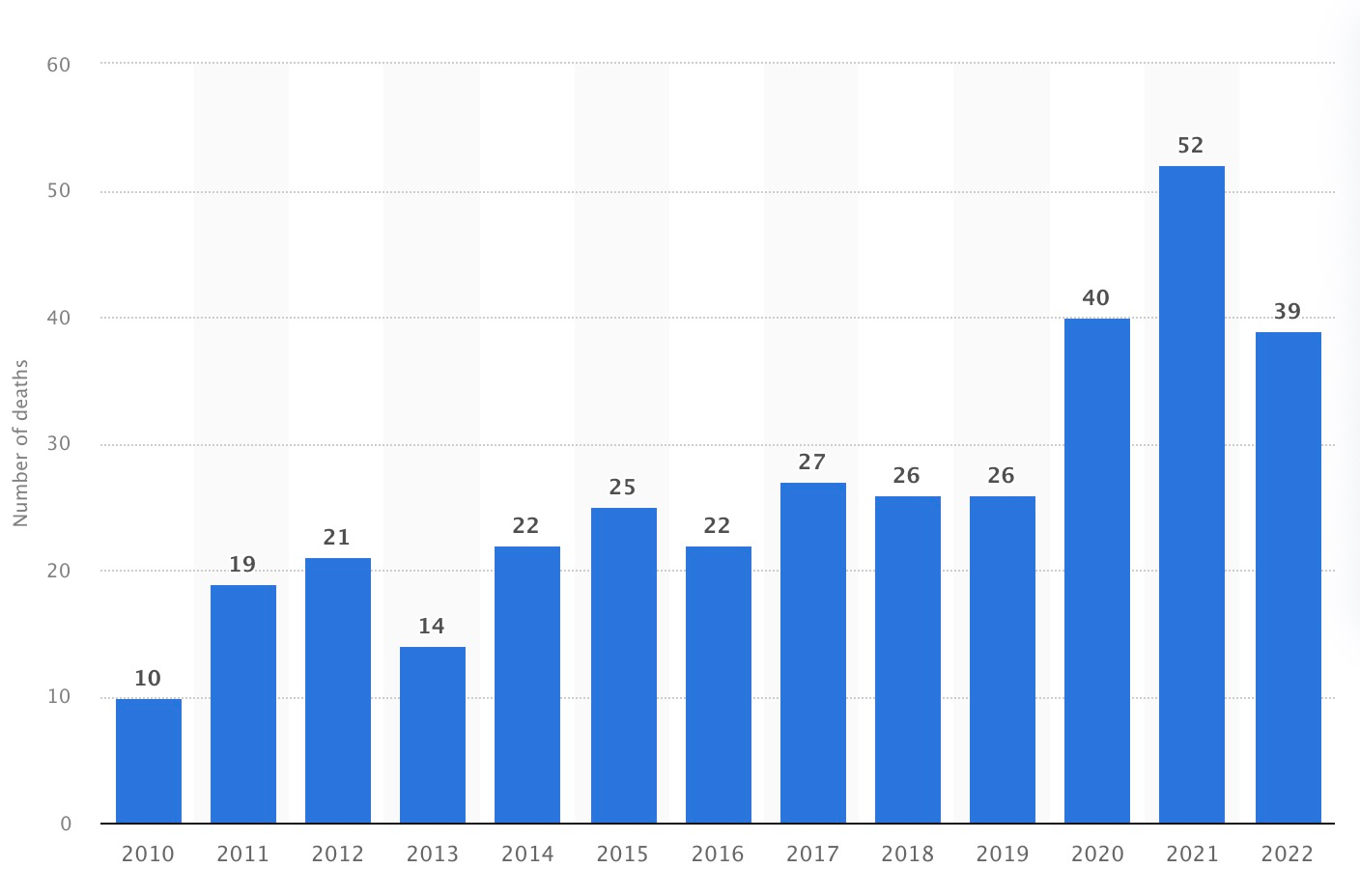

When it comes to assessing a government's performance, economic well-being is an important variable to consider, although it provides only a partial explanation of the state of affairs. Conversely, public perception of the government is often underestimated, even though it plays a crucial role in maintaining stability. In this respect, Macron is undeniably struggling and is regularly portrayed as an arrogant authoritarian with little regard for the lower classes. These accusations are not unfounded, but they tend to be bound to a one-sided narrative that cherry-picks evidence. Perhaps the most popular of these is the recurring comparison of Macron's government with fascism, an accusation often linked to the legitimization of police violence against protesters as a means of censorship. The French documentary “Un pays qui se tient sage”, literally “A wise nation”, provided an immersive coverage of these events, in particular the Yellow Vests movement – a series of protests that resulted in numerous injuries – emphatically presenting the series of events through a political prism. The police brutality covered in this documentary is undeniable and seemingly supported by the annual number of deaths related to police intervention in France during this period.

The rising number of deaths and injuries among protesters during Macron's presidency is quite alarming, but while these numbers are often reported by journalists, they are rarely contrasted with the fact that the number of attacks on the national police force has more than doubled in twenty years. Admittedly, these figures come from the Ministry of the Interior, which has been criticized for using unreliable statistical methods. In addition, it's difficult to establish a direct link between the overall increase in violence against the police over twenty years and the recent increase in deaths during protests. Nevertheless, much of the explanation lies in the fact that Macron's government has faced an unprecedented number of violent protests, which has unmistakably resulted in more incidents.

Another popular criticism of Macron lies in his rhetoric, which is commonly referred to as vacuous and often underscores the assumption that he's a deceitful individual by reducing him to his former position as a banker – an indictment closer to conspiracy theories than supported by serious evidence. Many of these kinds of accusations are usually framed as a long list of lies he allegedly told to get himself into a position of power to serve the interests of the rich, and are articulated by pointing out contradictory statements he has made as an attempt to emphasize inconsistencies between his words and actions. Even if the most honest politicians are unmistakably prone to incoherent decisions, and assuming that Macron perpetually lies, this should be reflected in a purely quantitative analysis. Unsurprisingly, the number of campaign promises made by Macron has been largely kept and closely comparable to those of his predecessor, François Hollande.

Macron has been repeatedly portrayed as an autocrat due to several reforms that have been enforced with the use of 49.3 – a bill that allows the government to impose the adoption of a law by the Assembly without a vote. But historically, the use of such a law has been much more common in the past, undermining the argument that France has become anti-democratic. And paradoxically, the anti-democratic criticism of 49.3 is mostly voiced by the left, which also tends to forget that, throughout history, the same law has been used 33 times by a right-wing government leader as opposed to 56 times by a left-wing government leader. More importantly, a clause like 49.3 may be unique to the French Constitution, but many democracies have inherited – thanks to the French – similar means of balancing power.

Admittedly, I concede that Macron has surrounded himself with questionable politicians, as many of them have been placed under investigation, a concern that resonates with the rise in probity offenses, which have increased by 28% between 2016 and 2021. However, it is important to highlight that this increase is most likely due to the fact that the government has become more efficient in fighting corruption as a result of the establishment of three institutions specialized in this matter: the High Authority for the Transparency of Public Life (2013), the Central Anti-Corruption Office (2013), and the French Anti-Corruption Agency (2016).

France is undeniably showing optimistic results from an economic perspective, but it's largely dismissed on the adverse political sides and in the media. A view that doesn't seem surprising, as the country's political influence is deeply rooted in socialism, which manifests itself in a latent anti-market sentiment – especially when Macron is commonly perceived as serving the rich while holding disdain for the lower class. Perhaps one of the most controversial moments of his presidency was his response to someone claiming a lack of job opportunities, “I can walk across the street and find you a job” – suggesting that many business owners were struggling to employ staff – a statement that resonated as incendiary and became infamously associated with him. And even though Macron's communication style is infinitely softer in comparison to someone like Donald Trump, it elicits comparatively hostile reactions like those observed on the other side of the Atlantic.

Opposition as tribal signaling

While it's undeniable that anti-Macron sentiment exists in varying degrees of intensity, it appears to be clustered in specific political factions or geographic areas rather than globally. On average, metrics such as popularity ratings place Macron as slightly better than his predecessors, and his politics seem to be overwhelmingly supported internationally, according to how French people living abroad voted. As someone who has visited and lived in thirty countries, the results don't come as a surprise, mainly for two reasons: the French welfare system is in many ways incredibly generous; people's political views are influenced by their environment. The electoral map, however, is painfully clichéd; my heuristic guess is that French people living in Iceland are likely to believe that electing a populist like Melenchon will lead to the cancellation of the national debt – as if France was a country of 300,000 inhabitants. Similarly, those living in sub-Saharan countries vote far-left because they are subject to social desirability from their peers who could benefit from the French welfare system, and those living in Russia probably think that the French government is too soft in every respect.

In France, the granular geographic comparison between the last round of elections is strikingly relevant to grasp how the rise of the opposition has grown organically. Although identifying the main driver behind this trend is a tedious task, as it could be attributed to a multitude of factors such as growing inequalities, immigration, social media and continuous information channels. Therefore, I'm uncertain whether I can confidently draw a causal explanation for Marine Le Pen's rise, but my intuition would attribute the spread of the party's influence to a social contagion phenomenon, or what I would call the “blob effect”. Marine Le Pen's rise appears to be sporadic, with unconquered territory getting contaminated from neighboring provinces – presumably because people are more susceptible to the influence of those who live close to them. A scenario that seems more plausible when we consider that Mrs. Le Pen's party scored much lower internationally, but still managed to occupy second place.

Historically, Le Pen's party was considered forbidden by the overwhelming majority of the French, although many people couldn't provide a rational explanation as to why it was dangerous to vote for it. In recent years, the banned party has gained popularity while softening its language to become much closer to the traditional right. Since most people's political beliefs are initially grounded in their core values, a bi-partisan political system is generally conducive to effectively directing people's votes according to their preferences. In the case of France, which now has four major right-wing parties that seem to overlap, developing a nuanced understanding has become more complex. I wouldn't be surprised if, in a blind test scenario, most voters could no longer tell the difference between the Republicans, the National Rally, Renaissance, and Reconquête. There are good reasons to believe that this paradigm shift has given more power to social conformity, as people tend to rely more on others' choices in the face of ambiguous decisions, and consequently has facilitated the normalization of extremist parties like the National Rally (Le Pen) in rural areas where they were previously constrained by a deontological clause.

Despite a massive approval of Macron by the French living outside of France, the French president remains misunderstood by a part of the French citizens, nor does it seem to be reciprocal. Many of the criticisms that have been made fall short of objectivity, or attach too much importance to criteria that are irrelevant for guiding public opinion towards effective policies. The economist Bryan Caplan famously demonstrated with empirical evidence in his book The Myth of the Rational Voter that most democracies are flawed because of the average voter's poor understanding of economic principles. And conversely, the more educated voters are, the more they tend to think as economists and elect politicians who make decisions that are better for them in the long run. This theory partially explains why people tend to make irrational political decisions, but it also fails to explain the rise of extremism in France and, more broadly, in Europe, despite the fact that the educational system in most OECD countries has remained stable over the past decades. Understandably, the French welfare system didn't start to perform well with the arrival of Macron, but it would be equally dishonest to pretend that it has been dismantled since he came to power. The reality is probably that France is doing fine, at least better than many of its peers by objective standards, but unfortunately, this has had little effect in addressing the country's growing tensions.