A Response to France’s Best-Selling COVID Skeptic

The Book My Contrarian Friend Loves—And Why It’s Wrong

I’ve been arguing with my favorite contrarian friend about the usefulness of COVID-19 vaccines and, more broadly, about the implications of the pandemic. Part of our disagreement stems from trusting different sources and by extension, different interpretations. I generally trust institutions and regard mainstream media reporting as reliable. On the other hand, my friend is more open to the idea that sometimes, the elites can be wrong, and dissident voices are those who can provide enlightenment—ultimately, we’re very much aligned on free speech principles.

I asked him about his favorite sources, and he mentioned Covid 19: What Official Figures Reveal by Pierre Chaillot. By Googling it, I noticed that it figured among the best-sellers while the author is highly regarded by the French seeking rational arguments that fuel an alternative narrative about the COVID-19 pandemic.

I felt overwhelmed parsing each section—all filled with charts. I tried summarizing the most important parts by using multiple Claude Code agents to aggregate each chapter into a big document. It was even more intimidating, and the chance of changing my friend’s view would drop significantly if he discovered I hadn’t read the book.

To be frank, I’ve read maybe half of it. I skipped parts that were redundant or too specific, focusing on its core claims—what I believe is worth debunking.

No excess mortality

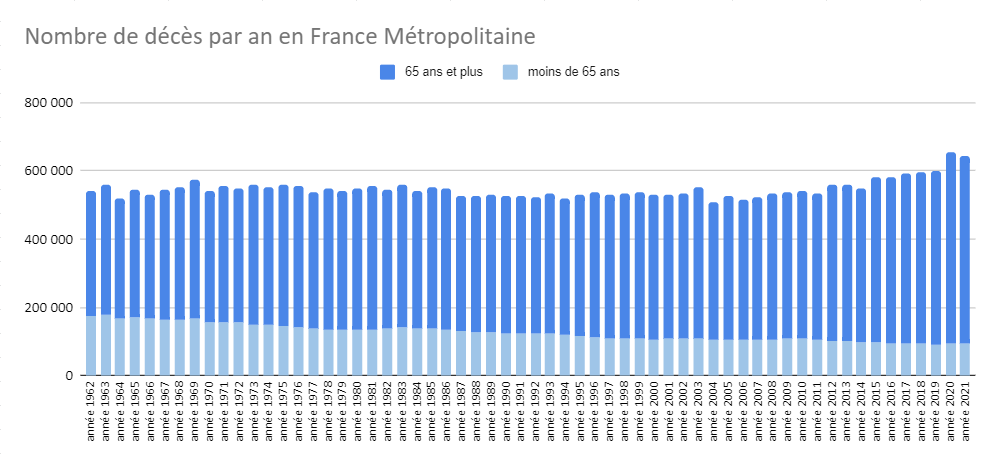

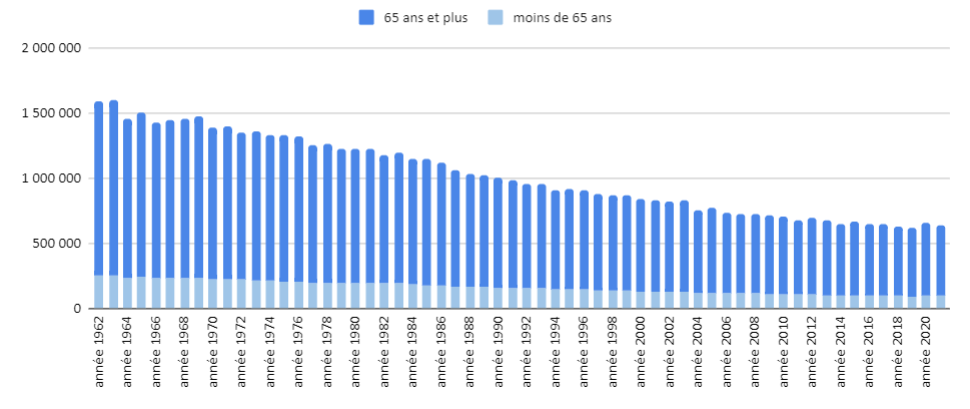

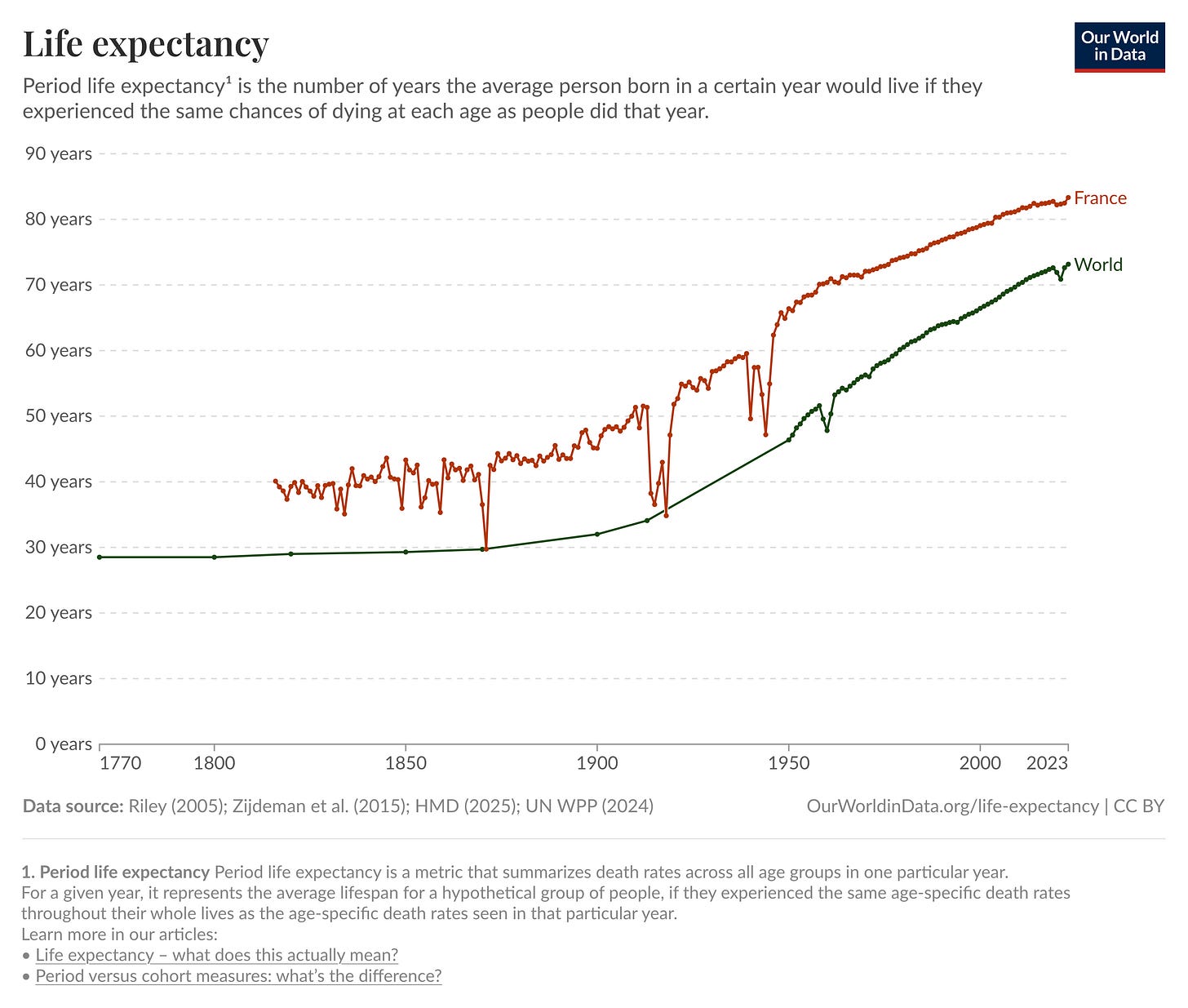

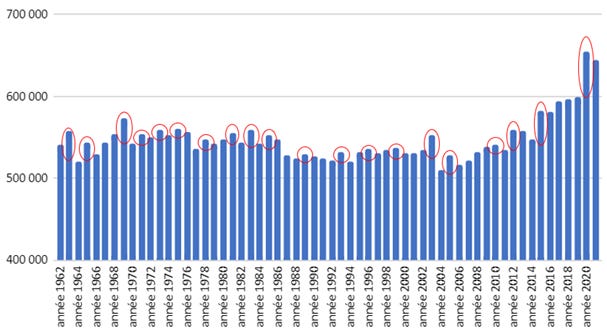

The first and likely most important argument advanced by Pierre Chaillot is that there hasn’t been an excess of mortality during the COVID pandemic. According to the author the way French national statistics display mortality over years is misleading, because of its aging population that is shifting the age pyramid distribution over time. This phenomenon naturally increases the deaths among the elderly, therefore counting absolute deaths is irrelevant; what would make sense is to standardize death counts according to the French demography of 2020. In other words, deaths from previous years should be proportionally adjusted to the French age distribution from 2020.

This reasoning is flawed. Life expectancy has grown continuously—people live longer now than they did five, twenty, or fifty years ago. Therefore the French age distribution for 2020 is intrinsically linked to medical progress. In 1962, a 70-year-old had a significantly lower chance of survival than in 2020. Standardizing death by 2020 means applying a proportion of death per age bracket from the previous years—that was obviously higher—using a more recent and older demographic distribution that wouldn’t be possible at that time.

The author also reviews the official numbers about the mortality difference between 2020 and 2019 (9% increase), claiming the “surplus” of mortality for 2020 is likely explained by the harvesting effect—a well-known and studied effect responsible for the fluctuation in annual deaths. The harvesting effect is cyclical (typically every five years) and related to various factors like heat waves or flus that can significantly increase the number of deaths from one year to another. Pierre Chaillot uses the year 2015 (the previous harvesting year) as a model of comparison for 2020, suggesting the increase of deaths is likely marginal or inexistent after taking into account the harvesting effect, and the aging of the French population, concluding that the years 2019 to 2021 represent the least deadly three-year period in French history—after taking into account the standardization.

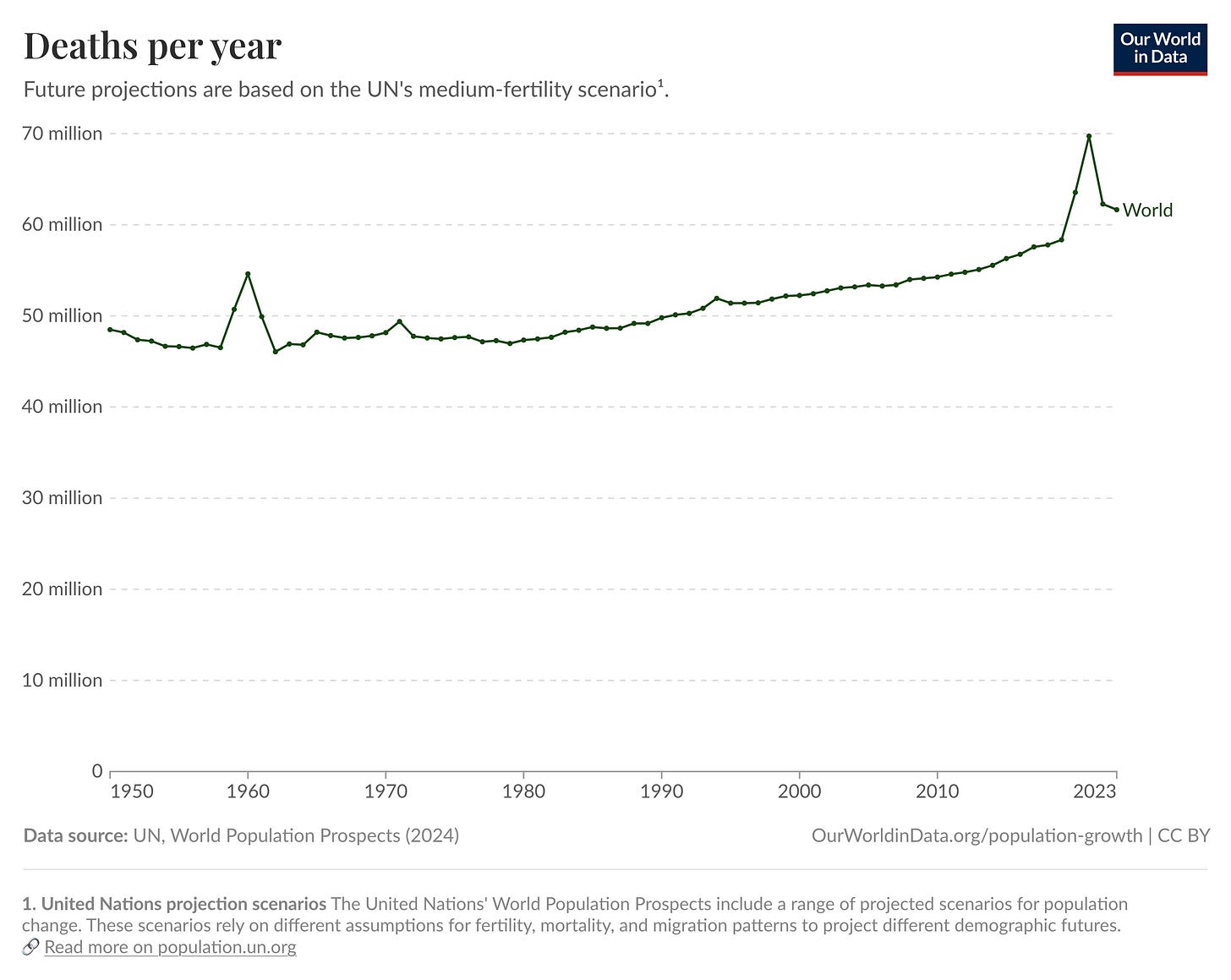

However, no official source designates 2020 as a harvesting year. And the French population aging between 2015 and 2020 (+2% for ages 65+ and +0.3% for 75+) seems too small to explain the mortality spike. The stronger counter-argument here is that, if COVID-19 wasn’t responsible for an excess of mortality in France (which counts among the highest number of elderly citizens and subject to seasonal flu activity), how did the rest of the world—with much younger demographics—see a significant increase in deaths during the same period?

Tests don’t detect illness

Pierre Chaillot extensively tries to explain how RT-PCR tests are flawed as their mechanism of action works by amplification cycles and this creates uncertainty which also increases the chance of false positives; that a positive Covid-19 case is not necessarily a sick person, but someone who has been tested and whose test result is positive, arguing that many perfectly healthy people test positive while sick people can test negative.

There is no link between the result of a test and the fact of being sick.

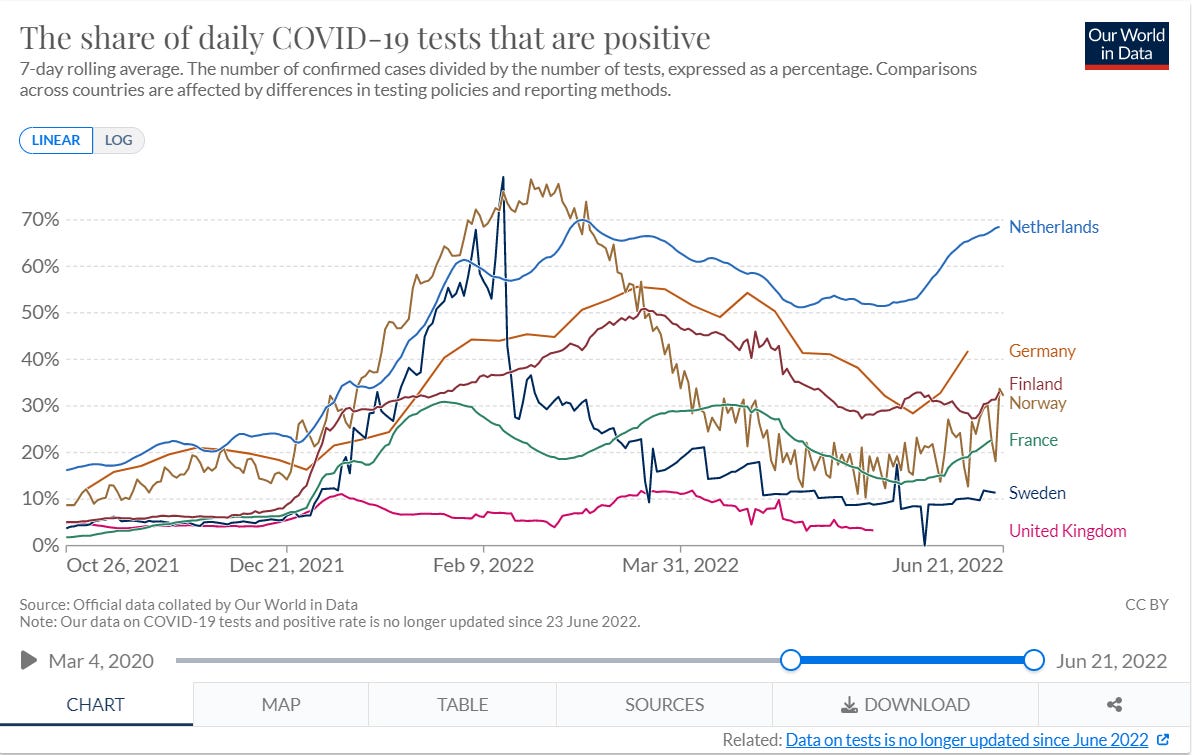

He concluded by presenting this chart, mentioning the case of the Netherlands (70% positive tests), arguing it would be impossible to have such high rates if PCR tests were reliable.

First, presenting this chart without mentioning that most tests used were antigen tests—not PCR—obscures the full picture. Antigen tests are less sensitive but correctly rule out infection in 99.5% of cases.

Second, the high wave coincided with the Omicron variant which was much more contagious but less dangerous.

Third, RT-PCR tests work by first converting viral RNA into DNA, then amplifying it to detectable levels. This detects the presence of viral genetic material, which understandably does not determine whether the person is sick—because that’s not the purpose of the test.

While it’s true that testing positive doesn’t translate to expressing symptoms (and vice versa), Chaillot’s conclusion is misleading. PCR tests remain the gold standard because they are highly reliable and accurate. When samples containing the virus are properly collected, PCR detects it with near 100% accuracy.

A French Health Authority (HAS) meta-analysis of 65 trials and 19,500 paired tests found RT-PCR sensitivity (the ability to correctly identify infected people) of 92% [90-94%] for nasopharyngeal samples.

While no test is 100% reliable, claiming that testing should equal detecting sickness misses the point—the main purpose is to identify infected individuals who are or may be contagious.

Vaccines don’t work

Chaillot’s first criticism against the RNA vaccines is about the integrity of the pharmaceuticals industry, highlighting the fact that Pfizer has been involved in many judicial cases, including one of the largest health care fraud settlements where Pfizer paid $2.3 billion for fraudulent marketing. He’s also questioning the potential conflict of interest involved in pharmaceutical companies financing their own medical studies.

It is aberrant that drug validation by control authorities is based on studies financed by the laboratories themselves, who wish to sell their products.

It’s true that pharmaceutical companies fund their own trials, which creates potential conflicts of interest. But considering that a full trial suite can cost around a billion dollars, it would be very difficult to find independent research, and letting that part be financed by governments instead would be incredibly inefficient and time-consuming. Besides that, financing your own study doesn’t mean you have a lot of freedom: clinical study processes like the FDA involve a lot of transparency and requirements, including pre-registration of trials, independent data monitoring committees, and regulatory agency review of raw data.

Chaillot also dismisses the effect of both Pfizer and Moderna vaccines on the basis that their trials haven’t shown any reduction in mortality as the number of deaths is the same in the vaccine and placebo groups.

Neither trial showed mortality reduction. Efficacy claims based solely on positive PCR tests, not actual death prevention.

To cite the Moderna paper: “a total of 32 deaths had occurred by completion of the blinded phase, with 16 deaths each (0.1%) in the placebo and mRNA-vaccinated groups, no deaths were considered to be related to injections of placebo or vaccine, and 4 were attributed to Covid-19 (3 in the placebo group and 1 in the mRNA-1273 group)”—the Pfizer study presents similar numbers of deaths.

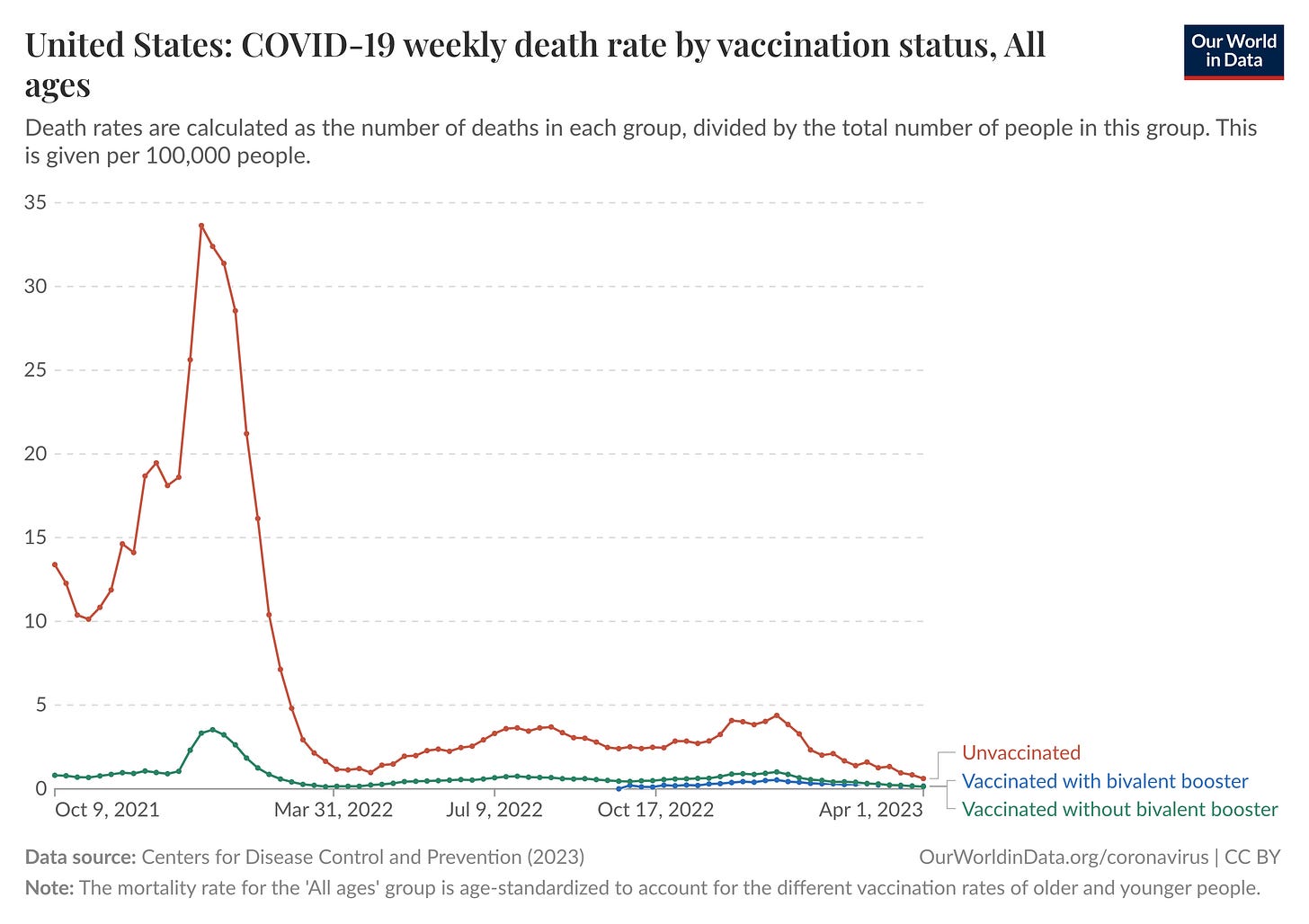

Chaillot correctly cites the death numbers but fundamentally misunderstands clinical trial design. The trials had ~30,000 participants followed for 2-5 months. With only 32 total deaths in Moderna (0.1% mortality), the trials had zero statistical power to detect all-cause mortality differences. The trials were designed and powered to measure symptomatic COVID-19 reduction—which they demonstrated with 93–95% efficacy and high statistical significance. Death prevention was measured post-authorization in real-world data with millions of people over years. The chart below shows COVID-19 death rates in the United States: unvaccinated individuals had death rates 5-10x higher than vaccinated individuals during 2021-2023.

Denialism, not skepticism

Admittedly, I’m far from neutral and expressed skepticism before reading Chaillot’s work, but I found myself baffled by the degree of denialism presented there. Yet there is plenty of room for valid criticism of pandemic policy: Would enforcing lockdown on people 65 years or older be enough? Was the vaccine mandate counter-productive in maximizing vaccination rates? Were vaccine boosters for young adults worth the risk-benefit tradeoff? Chaillot addresses none of these questions and instead, relentlessly misinterprets the official numbers of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, it’s hard to believe Chaillot accidentally omitted every piece of contradicting evidence while displaying such statistical illiteracy. Throughout his book, Chaillot keeps denying the number of deaths, the validity of testing, and the vaccine efficacy. A strategy that was instrumental in laying a foundation for a bigger claim: There has never been a pandemic.